Courageous conversations

Literary translator Petra Pugar shares her own Croatian excerpt from Alasdair Gray’s 1982, Janine and describes her process for translating works like Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain and Young Mungo.

Listen to Petra’s answers or read what she says.

Please introduce yourself to us?

My name is Petra Pugar. I am a literary translator from Croatia and also a PhD candidate at the University of Zagreb, Croatia, writing my dissertation on Scottish literature, notably Alasdair Gray. So far I have translated some 8 novels and in terms of Scottish literature, I translated Douglas Stewart's Shuggie Bain into Croatian and I'm currently translating his second novel, Young Mungo.

What is your translation process?

First of all, there is the crucial question of what kind of project I'm translating. Am I translating a novel, a poem, a children's book or a film? Because each of those forms and their subgenres, has their own technical specificities that often call for vastly different choices as a translator.

So let's say I am translating a novel. To be a good translator, one has to be a careful reader and a curious researcher. This is why I approach every novel in such a way that I first read the book, like a reader would do.

At the same time I try to find out as much as I can about the novel itself, to make sense not only of its surface level content and plot but also the wider cultural context. What influenced the book, what period does it reflect, what is its place in the author’s catalogue, it’s national literature and world literature? What is the author playing with or exposing and what makes this text a literary text?

I see it as similar to getting to know a person. What are this person’s strengths and weaknesses, what are they showcasing and what is visible only at a second or a third glance? Some books are more about the language and the form, some are more about the plot, some are about the emotions and so on. This is of course not always clean cut but rather a mix. But you have to pinpoint the things the writer was focusing on the most when writing the book.

On the other hand I think about the effects that I feel as a reader, the effects that I want to recreate for my Croatian readers. Sometimes that can mean not reading some parts of the novel before translating them. For example, if I see there will be a very emotionally charged speech in the novel, I try to translate that part during my first reading. So that I write while its impact, and my own emotions, are still fresh.

How do you manage your time as a translator?

Well it is a lot of thought and there are some challenges, in terms of the time I have available for each project. Because if it were a true passion project for me, it would take much more time! With the deadlines, with the publisher’s expectations, it has to be reduced a bit. So, I have to make do with the time I have.

For a novel for example, I have some 5 months on average and the research part is done during the first month. Then I start translating bits and pieces, returning to them again and, let’s say, that’s the timeframe. Depending on how many projects I’m working on, it changes.

How do you stay true to the author’s own voice?

One thing I noticed with my translation process is that every new book I am translating I have a feeling that I sound like a different writer, like a different author. I’m writing in a different way and the output and project are different among themselves.

I believe this comes naturally, this comes as a conversation with an author. I am not asserting my own voice, I am at the service of an author, of the book, of the novel and I have to be flexible and let the author’s voice permeate me. So this all sounds quite intangible but it happens organically, I would say. As you research an author, as you read about his process and as you read the book itself.

It’s quite like the reading process as well. When we read a book, we let this book enter us. Each author has their own cadence, their own rhythm, their own sentence structure. So yes, it’s different for each and every author and I think that makes a good translator. Not that I’m calling myself a good translator, but I hope to be one.

What challenges did you face translating Shuggie Bain?

The biggest challenge with translating Shuggie Bain was the idiom. The different language is mostly present in the dialogues that signal the difference, the social class, the character’s background and when translating this into Croatian I cannot use a recognisable, existing Croatian dialect. Because that would mean adding a layer that is not there, another cultural context and too much locality – that is a different locality from the Glaswegian locality.

But I did have to somehow signal the difference from the narrator’s standard language and this is where I created my own system, that works internally for the world of the book. So I shortened the length in some syllables and vowels and I used some slang words from the 80s and the 90s, since that is when the book takes place.

Another challenge was to present the wider Scottish cultural context the book is permeated with. So besides having done scholarly work on Scottish literature, I’ve been lucky enough to have visited Scotland and Glasgow on multiple occasions and this made me embody the experience, as a translator. And I’m convinced that my lived experience helps me to create an authentic translation, even on an unconscious level.

I’m also working at a time when my readers can look up the places from the book on the internet - see the maps, see the pictures, so that the places are more than just words on a page. And of course if the reader ever comes to Glasgow after reading Shuggie Bain, they will have a feeling they know the soul of the city a bit more than your average tourist and that is something I hoped to achieve.

Of course finally there is the emotions and the struggles of the characters. Who are very strong and they’re the backbone of the novel. Their internal fights are what Shuggie Bain is about and I decided this cannot be sacrificed, in terms of translation. Other things can be sacrificed, but the emotion cannot be sacrificed.

I think I achieved that emotional effect because the readers mention being stunned at how Scottish people are so similar to Croatians in terms of household dynamics, political reality of a post-industrial period, etc. But also little things like humour and hard things like alcoholism, and this is something that resonates. As a translator my goal is to find that common thread and that feeling that makes a book stand out from being just words on a page, in the Croatian language.

What did you sacrifice for the sake of the emotion in Shuggie Bain?

Sometimes it’s a word that would stick out. I mean, I try to keep as much as possible but not at the expense of the main emotion or the main message. So sometimes you find a word that sticks out, that doesn’t fit into Croatian, or that has to be replaced with another word - some lexical choices, some formal choices. I don’t change the book but there are slight differences, slight sacrifices that always happen but I try to make them as few as possible.

How does your voice as a translator differ to the author’s voice?

That’s the luxury that writers have! They are compelled to develop their own voice, to be different to the others, to be very, very specifically recognisable. Me as a translator, I have to do the opposite.

I was talking to a friend the other day. She read Shuggie Bain in my translation and she had an interesting comment. She said that when she started reading the book she thought she was going to hear my voice and my words, knowing that I am her close friend and she talks to me every day. But I disappeared and she just got immersed in the book after 2 or 3 pages. Those kind of things tell me that I have done my job.

What challenges would you face translating Alasdair Gray’s work?

The biggest challenge with Gray would certainly be his immense erudition. So as a translator I cannot hope to share a fraction of his knowledge, or to have read a fraction of the books he read, but one can be aware of it and always be on the lookout.

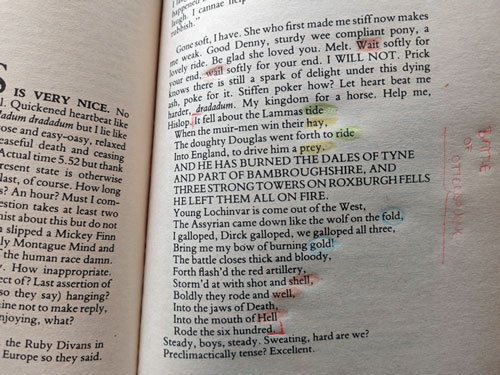

Every word can be a quote, either direct or twisted, as we will see in 1982, Janine from the Battle of Otterburn - and it is often not even marked as a quote. So a translator’s task is to recognise the reference, find out if there is a known, pre-existing translation in their own language and if not, translate it on their own. Since I am also a Gray scholar, I can use my research on Gray when translating him and I can use my translation skill when researching his works. Someone said that translators make the best readers and I would agree with them!

Can you describe the passage you’ve translated from 1982, Janine?

The passage in 1982, Janine that I translated for this conversation is the part where there is a sex scene and it’s merged with a quote of an old epic poem. So it’s a challenge, and it’s interesting, and I hope I did something good with it.

When I am dealing with an author I know a lot about, like Gray, my approach is such that I try to create a balance, a sort of a distance, so that I retain some freshness and not get overly technical about it. That means that after doing all of my research, I try to imagine reading a passage and Gray himself, for the first time. Because that is what my reader will experience as well.

I have to say that since I have not translated 1982, Janine yet, translating just a selected paragraph without previously developing this translator’s relationship with the book, will necessarily have a different result than what it would have been if I had translated the previously 175 pages. Because this relationship is something that develops organically and this is why with a lot of books, I have to go back to the first 20 pages after having translated the whole thing. But I can give it a try none the less, as an exercise.

Can you read us your translation of Galloping from 1982, Janine?

I’m going to read a passage from Chapter 11 in 1982, Janine, Galloping, on page 175 starting with ‘Gone soft I have…’

Omekšao sam. Ona koja me najprije ukrutila, sad me oslabila. Dobra Denny, stameni i uslužni poni, krasno jahanje. Budi sretan što te voljela. Rastopi se. Meko čekaj da dođe kraj, meko jecaj da dođe kraj. NEĆU. Kita zna da pod tim pepelom još tinja iskra užitka, ruje za njom. Ukrutiti žarač kako? Nek me srce udara jače, dradadum. Moje kraljevstvo za konja. Pomozi mi, Hislope. Zbilo se pred blagdan zvani Lammas

Kad muževi s vrijesišta žanju svoje žito,

Vrli je tad izjahao Douglas

U Englesku, plijen gonio hitro.

I SPALI ON DOLINE TYNEA

I DIO BAMBROUGHSHIREA, I

TRI JAKE KULE ROXBURGH FELLSA

SVE IH OSTAVI U PLAMENU.

Mladi Lochinvar siđe sa zapada,

Asirac kao vuk na stado napada

Dadoh se u galop, tako i Dirck, u galopu sva trojica,

Daj mi moj luk od gorućeg zlata!

Bitka se zadjenu u metežu i krvi,

Crvena artiljerija dušmanina smrvi,

Grunu sačmom i barutom,

Hrabro ujahaše

U ralje Smrti

U gubicu Pakla

Njih šest stotina.

Mirno, dečki, mirno. Znojimo se, i to obilno, zar ne?

Predklimaktično napeti? Odlično.

So this ends with ‘Pre-climatically tense? Excellent!’

This is Alasdair reading the same passage from 1982, Janine

Gone soft, I have. She who first made me stiff now makes me weak. Good Denny, sturdy wee compliant pony, a lovely ride. Be glad she loved you. Melt. Wait softly for your end, wail softly for your end. I WILL NOT. Prick knows there is still a spark of delight under this dying ash, poke for it. Stiffen poker how? Let heart beat me harder, dradadum. My kingdom for a horse. Help me, Hislop.

It fell about the Lammas tide

When the muir-men win their hay

The doughty Douglas went forth to ride

Into England, to drive him a prey.

AND HE HAS BURNED THE DALES OF TYNE

AND PART OF BANBOROUGHSHIRE, AND

THREE STONG TOWERS ON ROXBURGH FELLS

HE LEFT THEM ALL ON FIRE.

Young Lochinvar is come out of the West,

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

I galloped, Dirck galloped, we galloped all three,

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

The battle closes thick and bloody,

Forth flash’d the red artillery,

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldy they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Steady, boys, steady. Sweating, hard are we?

Preclimactically tense? Excellent.

What issues did you face in your 1982, Janine translation?

One of the issues I had was how to capture Gray’s playful voice. His sentences are sometimes not quite ordinary. He twists them and I have to do the same without them sounding just wrong in Croatian. For example ‘Stiffen poke how’, or ‘Let heart beat me harder’. It’s not ‘let heart beat harder’ but ‘beat me harder’, so this is like a little word play of his.

I also have to pay attention to the way that words are onomatopoetically charged, the sound of them. For example he uses the verbs ‘wait’ and ‘wail’. It’s like poetry inside prose and I decided to use the words ‘čekaj’ and ‘jecaj’ in Croatian. Because they have practically the same meaning and some of the same sounds.

As I said, Gray is very knowledgeable about older literary works. He uses quotes and here he quoted an older text, which hasn’t been translated into Croatian and I had to create a translation within translation. What I did to signal this difference since there are no footnotes, there are no quotation marks, is to change the register when it switched to the epic poem. I used archaic Croatian expressions and verb forms used in epic lyric poetry in Croatian.

It was a challenge to create a rhythm and a rhyme of an oral text. To achieve rhyme some slight lexical changes have to be made and this is always a game. You have to switch from prose translator to poetry translator and there is always this line that a translator needs to tread in order to achieve the best of both worlds. Which means to retain the formal and stylistic elements, as well as the content itself.

So my translation, as you heard, will not have the exact rhythm of Gray’s original text because the cadence, the intonation, the words themselves in Croatian are different from English. What I can do is use the repertoire I have at hand to create an equivalent and in doing that, during my process, I have to read both the English text and my versions out loud. So sometimes one has to be an actor as well!

What is at the heart of literary translation for you?

What I consider the most beautiful and the most difficult side of literary translation is the fact that there is no correct, ideal version that you aim to achieve. Because if it existed somewhere, it could have been rendered by a computer. If we look at writing as a creative, artistic process in which no 2 authors can write the same book, the translation process shares quite a lot of similarities in that respect.

There are no 2 translators, no matter how educated and talented, that would produce the same translation of a literary text. Something will always be lost and something gained and something will enrich the original version, in a similar way an adaptation into a film or a play enriches a literary work. This is not necessarily true for other types of translation that are not literary, that are more technical, and there the gap is much narrower.

But this is something I am always aware of when approaching a project. I have immense respect for the original and try to create its version in my language. But I am also aware that I am an active participant in this very personal and individual process. That I need to be brave enough to make my own choices and, in the end, defend them!