Pushing boundaries

Alasdair Gray’s engagement with disability-led theatre was radical for its time. But times have changed. Anita Sullivan (Freewheelers Theatre and Media Company) and Robert Softley Gale (Birds of Paradise Theatre Company) explore the adaptive capability of disability theatre, as it pushes the boundaries of what’s expected and uses digital tools to support creativity and accessibility.

Alasdair Gray: Working Legs – A Play For People Without Them

Freewheelers: Do Not Disturb

Birds of Paradise: Don’t Make Tea

Alasdair Gray’s revolutionary Working Legs

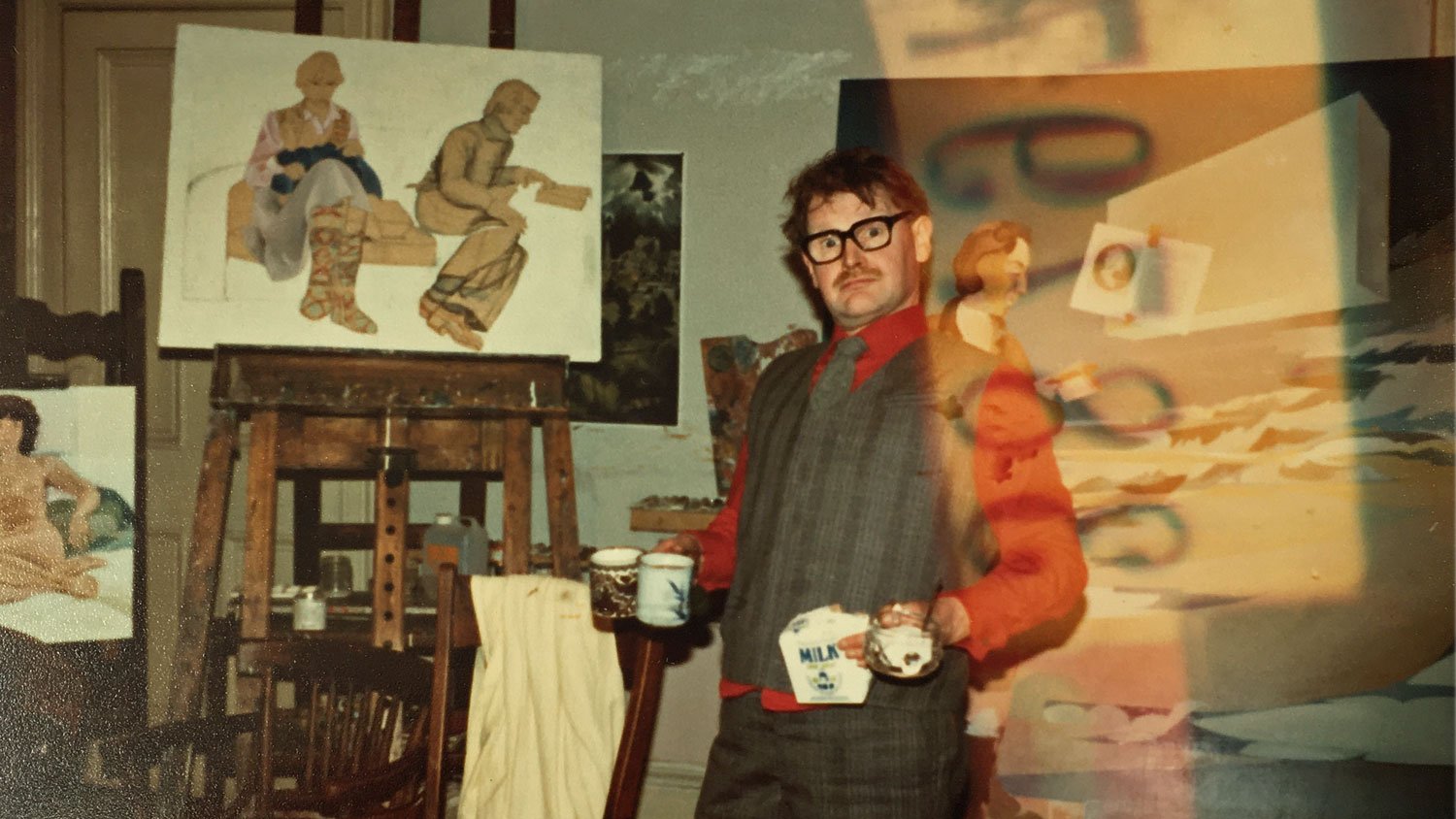

In 1997 Alasdair Gray created Working Legs, one of the first shows by Scotland’s Birds of Paradise disability theatre company. Alasdair gave them the copyright for the play and continued to be an active and outspoken supporter throughout his life. Current Artistic Director/CEO Robert Softley Gale talks about the play’s impact:

Robert says: At the time, Working Legs was pretty revolutionary in how it spoke about disability. Up to that point everything had been charity-model focused, asking ‘How do we help disabled people? What do they need?’ Working Legs flipped that on its head and politicised disability. And Birds of Paradise has continued that work for 30 years.

The play is set in an inverted world where wheelchair users are the norm and people with working legs experience barriers and stigma. Through workshops and rehearsals Alasdair worked on the concept and dialogue with the performers. Actor John Hollywood felt his part had been ‘written for him’ and found the experience empowering.

Alasdair’s name brought in an audience that may never have seen disabled actors perform before. But the play was analogue and wasn’t itself designed to be accessible. Contemporary disability theatre uses digital tools through development and performance to integrate accessibility. So how is that different today? This is a tale of two companies: Freewheelers and Birds of Paradise.

Multimedia disability theatre

Freewheelers Theatre and Media Company is a company of non-professional disabled performers. Their projects can be live or online. Live performances involve video, music, dance, puppetry and drama. Accessibility is supported by captions, British Sign Language Interpretation (BSL) and audio description. This level of multimedia and digital integration would be ambitious for any theatre company, but in Freewheeler-world anything that can be imagined is considered possible. It’s an exciting place to be.

Freewheelers: Do Not Disturb

Freewheelers: Steep Rain

Freewheelers: Destiny Betrayed

Like Birds of Paradise, Freewheelers create shows for, by or with the company. This is partly because off the normal-shelf playscripts are too limited to engage the talent in the company. If your first language is movement rather than spoken word, where do you fit? Or what about if you can improvise, but not memorise?

More importantly, the Freewheelers create plays about things that interest them. And this isn’t always disability! Freewheelers have travelled to the moon, ridden into the First World War (on an actual horse) and danced through the paintings of Degas. The collective mind is playful, subversive, a bit surreal and willing to tackle anything from Fawlty Towers slapstick to a Busby Berkley number. Freewheelers and Birds of Paradise shows are distinctive from start to finish, with digital technology helping to realise the impossible:

Robert says: Digital is very integrated into our work, almost as embedded as words and text. When it’s done well, it really works for an audience. But if you go and see a play and say ‘the set was fantastic’… that generally means the play was pretty awful. Similarly if you come home from a show going ‘wow, their use of technology was really great’ you missed the play. The digital elements should enhance the theatrical experience, they shouldn’t be the core of the show.

Examples of Birds of Paradise work: Don’t Make Tea and Purposeless Movements.

Do Not Disturb: A case study in Digital disability arts

Technology should support creativity without stealing the show. And support inclusion without losing the human connection. So how is digitally integrated disability theatre made?

Step 1: The starting point

Birds of Paradise is a disability-led professional company, building a bespoke cast and creative team for each project. Freewheelers is both a company and a community. The same core of disabled/ non-disabled/ professional/ non-professional practitioners and performers are involved from show to show. These differences shape our processes:

Robert says: When we use digital on stage, its one of the earliest conversations we have. We talk about the design, about access, how we’ll use of captions, BSL (British Sign Language) and audio description and how that will be relayed to the audience.

With Freewheelers it’s story-first. The core idea typically comes from the company. Do Not Disturb was inspired by out of body experiences of company members including Terri Winchester who survived a coma. Development was supported by director Brandon McGuire and Anita the ‘writer not in-residence’. Early devising was very analogue and involved long rolls of wallpaper-liner pinned to the walls, with me writing down the ideas as fast as they came. From this I would create and share a Word-document version, suitable for screen-readers.

Freewheelers storyboard

Step 2: Create a story

Over many weeks the company generated characters and scenes, ideas for music and song-lyrics, with professional creative support from composer Thomas Gray and choreographer Andrea Atkinson. Freewheelers has an inhouse tech team and can make and edit any film or animation needed.

Freewheelers media team

Freewheelers media team

Step 3: Get it rolling

Freewheelers meet weekly, so the development and rehearsal period is extended over months. For this reason Do Not Disturb used digital media for continuity. Workshops and work in progress were filmed, so we could review what’s been achieved and ‘democratically’ agree what to take forward; this also supported learning lines and choreography. Finally I assembled everything into a storyboard-script for rehearsal. The company has mixed abilities and this document helped focus and orientate everyone.

As a professional company Birds of Paradise has a short, intensive development and rehearsal process. So Robert’s process is different.

Robert says: In the rehearsal process, if you don’t remember something that happened it wasn’t meant to be remembered. If it’s good, you’ll recall it!

For some companies recall can be more difficult, for all sorts of reasons. We’ve all got video cameras in our pockets now, so we record everything that happens. But I rarely watch back what I record. I’ve got whole hard drives of videos I’ll never watch back, because the moment’s gone. It’s in the past.

Step 4: Make the show

During Do Not Disturb theatre ingredients such as lighting, sound, music, video, set and costumes evolved as part of the devising process and were refined to be accessible for the audience. With Birds of Paradise, this starts earlier.

Robert says: The director or theatre-maker’s job is to make sure the audience can see and hear everything. If they can’t they’re missing stuff and what’s the point? So when you’ve got an audience who are hard-of-hearing, deaf, visually-impaired or blind, then you have to open that up wider. If something visual’s happening on stage you have to ask, how do we describe that?

The performance space and props also have to be accessible for performers. In Do Not Disturb, a variety of prototypes for the puppet were created by Nick Barnes (award winning puppet designer and creator of the tiger in Life of Pi). Freewheelers made him rethink the fundamentals of the puppet, for example its height relative to the viewer, its sense of contact with the ground. With a disabled company puppeteering practicalities such as weight, balance and positioning of rods also had to be considered. Nick came to the radical conclusion that the puppet didn’t need legs. Working legs were not required!

“With puppetry you start in your imagination with a complete representation of whatever it is you’re making, human or animal. As you build you literally, physically cut away parts, so parts can move past each other, allowing for the ways our bodies stretch and flex. You’re abstracting and reducing as you do that. So I suppose removing the legs is an extension of that. You get to a point where you’re just… ‘we’ll get rid of those as well’ and the audience’s imagination will take us somewhere else. Removing the legs made it easier for the operators but it was also going to be an image that, in that context, might have resonance, some purpose beyond the script.”

After all this work, Freewheelers were able to tour Do Not Disturb to just one of three planned venues before Covid hit.

Freewheelers: Do Not Disturb

Freewheelers: Do Not Disturb

Freewheelers: Do Not Disturb

Zoom Cubed: Covid and digital theatre

Health risks made it impossible for the Freewheelers to meet, so we went on Zoom. It was a steep learning-curve and people needed help to set up and get orientated, but the company has a capability/ adaptability mindset. Within weeks they were using Zoom at a level I’ve seen few corporates attempt, with break-out rooms, whiteboards, polls, shared hosting, in-zoom recording and playback, with virtual biscuits passed from hand to hand across Zoom gallery-view. This creative and social connection was a lifeline for isolated company members.

In Edinburgh, Birds of Paradise were navigating the same journey.

Robert says: Birds of Paradise has 6 people, all working remotely. Everything we do is on Zoom, or using Cloud stories to collaborate and communicate with writers and designers. So that’s all very digital. It became more so over the pandemic. It’s interesting that now we have adapted the way we work to use digital and we can’t imagine any other way. But there are other ways. We did it before we had Zoom!

Freewheelers managed to keep going using Zoom, but it wasn’t for everyone. Some company members struggled with the intensity of the sessions, the many voices and faces on screen. The movement-orientated performers found it frustrating and excluding. But through collective effort we devised, workshopped, rehearsed, performed and recorded a play online. Zoom Cubed is about five different Zoom meetings get jumbled up in 3D space (including MI5, a dysfunctional disability hub and Viking re-enactment society). There’s a chase sequence across tumbling Zoom rooms. It’s bonkers.

Robert says: Over Lockdown and Covid, people were saying, ‘we’ll put everything online and that will fix everything. We can make it accessible, we can put it on YouTube.’ But that’s not theatre. For me theatre’s about being in the same space. It’s a very analogue experience.

Ultimately, Freewheelers used Zoom Cubed to process what was happening within the company and in the world at large, to keep connections alive. The creative, technical and communication lessons we learned together in adversity will bear fruit for many years to come. But Zoom Cubed remains unfinished. Digital was a huge enabler for Freewheelers across lockdown, but everyone is truly delighted to be back in-the-room again.

Going live again with Degas

The company returned to live performances in June 22, with Degas at the Harlequin Theatre Redhill, one of a handful of regional theatres with full back-stage accessibility for a large cast.

Freewheelers: Degas

Freewheelers: Degas

Freewheelers: Degas

In performance inclusive tools were extended to the audience with induction loops, sign-language interpretation, supertitles, audio description, a braille programme and pre-show touch-tours.

Robert says: Clearly accessibility technology is for the people who use BSL (British Sign Language), audio description or captions. But it can also demonstrate to the rest of the audience that these things really help in society. It shows how access can be done, how important it is, how funny it can be. The audio description for our production Don’t Make Tea made a lot of jokes. So the whole audience were laughing away at the description of what was going on. And that brings the room together, it brings people together. And for me that’s the important part.

Freewheelers always go beyond what is expected from disability theatre and I love working with a large multimedia company that blends live and digital elements so fluently. Like Robert, I’m curious about what digital tool for accessibility can do for narrative. Can audio-description and captioning become subversive paratexts or even alternative interactive narratives? Can they enhance the live experience for everyone, disabled or non-disabled? And is it possible to do any of that and still retain 360 accessibility? That’s an exciting creative conversation.

Alasdair Gray’s Working Legs now?

Written in 1997, Working Legs is a conventional analogue drama that was radical because of the story it told. But could Working Legs be staged in the same way now? Is it still relevant? Would it even be the same story?

Robert says: What Alasdair did is so interesting for someone who didn’t identify as being disabled. He was very aware of what we now call the Social Model of disability. This idea that it’s barriers in society that disable people, rather than them being disabled themselves. So it’s a flight of stairs that disables me, not my impairment. My impairment is always what it is, it’s the environment that makes me less able.

And what Alasdair understood implicitly in Working Legs is that the environment can change. Rules can change. The way society operates can change. And in the early ‘90s that was a radical way of thinking about things. Now almost 30 years later, it’s less radical. But we’ve still got a long way to go in making it real. So it would be interesting to see how an audience reacted to Working Legs nowadays.

Dedication in Alasdair Gray’s Working Legs

Part of the introduction to Alasdair Gray’s Working Legs

Title page of Alasdair Gray’s Working Legs

Alasdair Gray was boldly political, radical, playful and always challenging form. He pushed the limit of every medium he used. He questioned social norms and reimagined the human form. His mind worked in hyperlinked and digital ways before the technology was available to support it. He was an early Bird of Paradise and it’s easy to imagine him as a virtual Freewheeler.

Imagine what he might do with Working Legs today?

Explore more…

Who is Alasdair Gray?

Alasdair Gray is often described as a genius and regularly compared to the earlier writer and artist William Blake.

External links:

Writing Working Legs - watch an interview with Alasdair talking about the play and his development process.

Birds of Paradise Theatre Company - putting disabled artists centre-stage, creating world-class performances and supporting the arts sector to develop disability equality.

Freewheelers Theatre & Media Company - an inclusive arts company where artistic excellence goes hand in hand with learning and personal growth.

Nick Barnes Puppets is a UK based puppet making company.

Did you see Working Legs? Were you part of it? We’d love to hear from you.